Supporting Children to Develop Fine Motor Skills

Understanding Fine Motor Development

Fine motor skills involve the coordination of small muscles in the hands and fingers with the eyes. These skills are essential for tasks such as writing, drawing, buttoning clothes, and later, keyboarding. Strong fine motor skills developed in early childhood provide the foundation for academic success and daily living skills.

Fine motor skills are the small, precise movements that use the muscles in the hands, fingers, and wrists. These skills are essential for completing everyday tasks such as holding a pencil, cutting with scissors, doing up buttons, tying shoelaces, or using cutlery (Case-Smith & O’Brien, 2015). They rely on hand–eye coordination, strength, and dexterity, and develop gradually through play, practice, and real-life experiences.

Developing fine motor skills is important for children’s independence, as they support self-care activities like dressing, eating, and managing personal belongings. They are also critical for school readiness, particularly for handwriting, drawing, and other classroom tasks (Dinehart, 2015). In addition, fine motor development is closely connected to cognitive growth, as children learn to problem-solve, plan, and control their movements while engaging in fine motor play (Cameron et al., 2012).

Because fine motor development occurs at different rates for each child, it is important to provide a wide range of opportunities for practice through both structured activities, such as threading beads or puzzles, and everyday routines, such as cooking or helping with chores (Lorina, 2025). Encouraging these skills not only supports learning but also builds confidence and independence.

Examples of Fine Motor Skills in Action

-

Holding a pencil or crayon

-

Cutting with scissors

-

Stacking blocks or threading beads

-

Opening lunchbox containers

-

Turning pages in a book

-

Using playdough, tweezers, or tongs

Play Based Experience 1

Playdough Creations

Provide playdough with various tools like rolling pins, cookie cutters, and plastic knives. Children can roll, pinch, squeeze, and manipulate the dough, strengthening hand muscles and improving dexterity. Add small objects like buttons or beads for children to press into the dough, developing pincer grasp essential for pencil holding.

Play Based Experience 2

Threading and Lacing Activities

Set up threading activities using large wooden beads and shoelaces, or lacing cards with colorful yarn. These activities develop hand-eye coordination, bilateral coordination, and the pincer grasp. Progress from large beads to smaller ones as children's skills develop, preparing them for the precise movements needed in writing.

Why Fine Motor Skills are so important?

Fine motor skills are the small muscle movements in your child’s hands and fingers that they use every day when playing, eating, or getting dressed. Activities like drawing, building with blocks, threading beads, or playing with playdough all help strengthen these muscles and improve coordination.

These early skills are the building blocks for handwriting. A strong pincer grip, good hand–eye coordination, and control of finger movements make it easier for children to hold a pencil, form letters, and write smoothly. By giving children lots of fun, hands-on experiences, you’re helping them develop the confidence and strength they’ll need for writing in the school years.

Additional Fine Motor Skills Activities

Cutting with Scissors

Using scissors helps children develop bilateral coordination—using both hands together in a coordinated way, one to hold the paper and the other to cut. It also strengthens hand muscles and teaches control and precision, which are critical for writing and other school tasks (Schneck & Henderson, 1990).

Pegboards, Tweezers, and Tongs

Picking up objects with tweezers or placing pegs into boards builds grip strength and finger control. These activities refine dexterity, encourage correct finger positioning, and help children prepare for holding pencils and managing classroom tools (Berninger & Wolf, 2009).

Drawing, Colouring, and Scribbling

Early mark-making activities allow children to experiment with lines, shapes, and colours. These tasks support hand–eye coordination, strengthen control, and prepare children for formal writing. They also promote creativity and expression (Cameron et al., 2012).

Building with Blocks or Lego

Stacking, connecting, and balancing blocks promotes spatial awareness, problem-solving, and fine motor precision. These activities require children to manipulate small pieces carefully, improving finger strength and coordination (Rosenblum, 2018).

Everyday Tasks (Buttons, Zips, and Dressing)

Practical life tasks, such as fastening buttons or pulling zips, encourage independence while strengthening fine motor control. These skills are important for self-care and confidence, as well as preparing children for the demands of school routines (Case-Smith, 2015).

Linking Fine Motor Skills to Later Learning

Fine motor skills lay the foundation for handwriting and literacy. Children who have well-developed control in their fingers and hands are more likely to form letters correctly, write neatly, and sustain writing for longer periods without fatigue. Strong fine motor skills also support mathematics (e.g., using counters, manipulating shapes) and artistic expression.

Pencil Grip

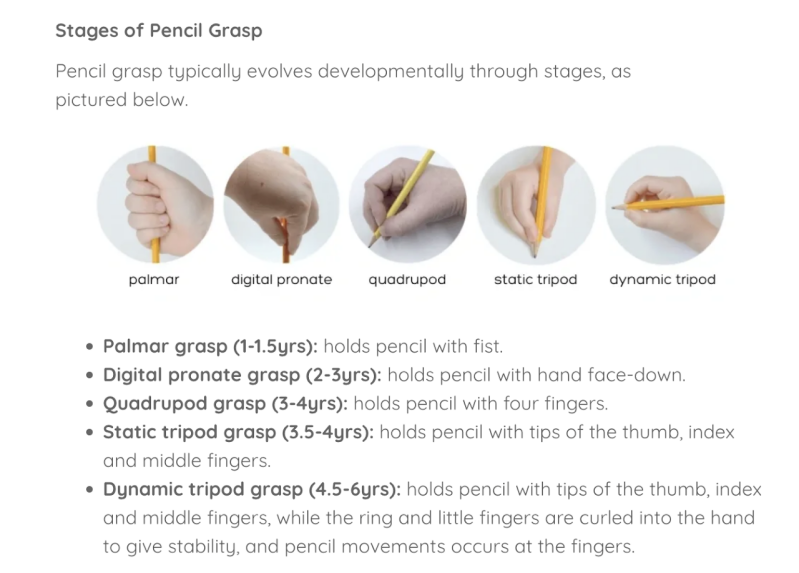

In the early years, toddlers often begin with a palmar supinate grasp, holding a crayon or pencil in their whole fist with the wrist facing upward. As they gain control, they shift to a digital pronate grasp, where the fingers point downward and the palm faces the page. At this stage, large movements from the arm and shoulder dominate, rather than fine finger movements (Schneck & Henderson, 1990).

By around three to four years of age, many children progress to a four-finger grasp or a static tripod grasp. Here, the pencil is held with three or four fingers, but the movement is still mostly from the wrist and arm rather than the fingers. This stage is important for early pre-writing tasks such as colouring and drawing basic shapes (Feder & Majnemer, 2007).

As children’s fine motor control improves, they usually develop a dynamic tripod grasp between four and seven years of age. This grip is considered the most efficient for fluent and sustained writing. In this stage, the thumb, index, and middle fingers move in coordination, and the pencil is controlled with small, precise finger movements rather than whole-arm motion (Berninger & Wolf, 2009).

Parents and educators can encourage pencil grip development through play-based fine motor activities such as threading beads, using playdough, cutting with scissors, or practising with tweezers. Providing shorter pencils and crayons also supports children to naturally adopt a tripod grip. Importantly, the aim should not be perfection but rather a comfortable, functional grip that enables children to write with confidence (Case-Smith, 2015).

Inclusive Approaches

Every child develops at their own pace, and some may need additional support. For children with ADHD, fine motor activities should be short, engaging, and hands-on, with opportunities for movement breaks to maintain focus (Cameron et al., 2012). Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder often thrive with structured, repetitive activities that build confidence in their fine motor abilities (Case-Smith & O’Brien, 2015). For children with dyslexia or dysgraphia, providing adapted tools such as pencil grips, slant boards, or thicker markers can reduce frustration and make writing tasks more accessible (Dinehart, 2015). By recognising diverse learning needs and making small adjustments, parents and educators can ensure every child experiences success.

When to Seek Professional Help

While all children progress at different rates, some may need additional support to strengthen their fine motor skills. Signs that a child may benefit from professional help include ongoing difficulty with tasks such as holding a pencil, using scissors, doing up buttons, or feeding themselves with cutlery. A child who avoids drawing or writing activities, or becomes frustrated when asked to complete them, may also require extra assistance. If these challenges persist beyond the expected age ranges, parents are encouraged to consult an Occupational Therapist or local child development service. Early support can make a significant difference in building confidence, independence, and school readiness (Feder & Majnemer, 2007; Kid Sense Child Development, 2024).

References

Berninger, V. W., & Wolf, B. J. (2009). Teaching students with dyslexia and dysgraphia: Lessons from teaching and science. Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Cameron, C. E., Brock, L. L., Murrah, W. M., Bell, L. H., Worzalla, S. L., Grissmer, D., & Morrison, F. J. (2012). Fine motor skills and executive function both contribute to kindergarten achievement. Child Development, 83(4), 1229–1244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01768.x

Case-Smith, J., & O'Brien, J. C. (2015). Occupational therapy for children and adolescents (7th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences.

Dinehart, L. H. (2015). Handwriting in early childhood education: Current research and future implications. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 15(1), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798414522825

Feder, K. P., & Majnemer, A. (2007). Handwriting development, competency, and intervention. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49(4), 312–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00312.x

Fine Motor Development Chart - Kid Sense Child Development. (2024, July 22). Kid Sense Child Development. https://childdevelopment.com.au/resources/child-development-charts/fine-motor-developmental-chart/

Lorina. (2025, January 5). 50 Fine motor skills activities - Aussie Childcare Network. Aussiechildcarenetwork.com.au. https://aussiechildcarenetwork.com.au/articles/teaching-children/50-fine-motor-skills-activities

Rosenblum, S. (2018). Development, assessment, and intervention of handwriting difficulties in school-aged children: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1450. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01450

Schneck, C. M., & Henderson, A. (1990). Descriptive analysis of the developmental progression of grip position for pencil and crayon control in nondysfunctional children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 44(10), 893–900. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.44.10.893

Create Your Own Website With Webador